Source: Hack a Day

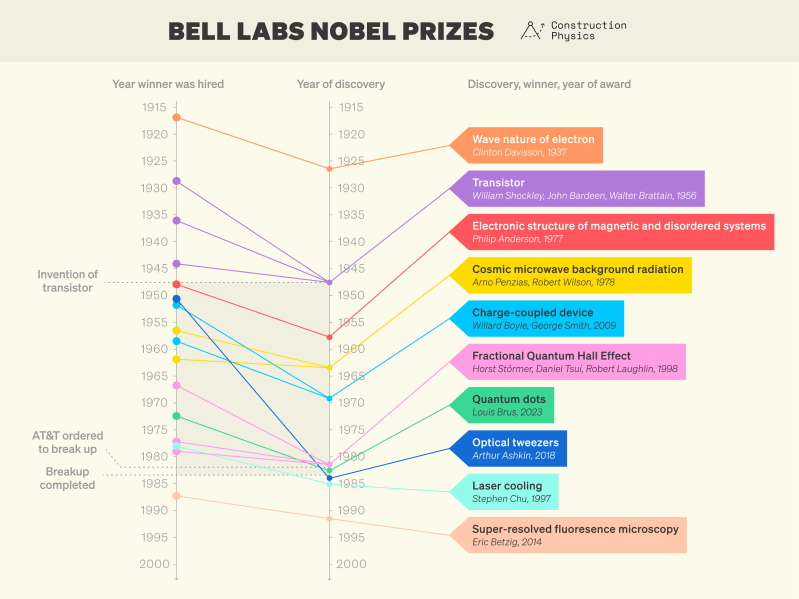

It’s been said that the best way to stifle creativity by researchers is to demand that they produce immediately marketable technologies and products. This is also effectively the story of Bell Labs, originally founded as Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc. in January 1925. As an integral part of AT&T and Western Electric, it enjoyed immense funding and owing to the stable financial situation of AT&T very little pressure to produce results. This led to the development of a wide range of technologies like the transistor, laser, photovoltaic cell, charge-coupled cell (CCD), Unix operating system and so on. After the break-up of AT&T, however, funding dried up and with it the discoveries that had once made Bell Labs such a famous entity. Which raises the question of what it would take to create a new Bell Labs?

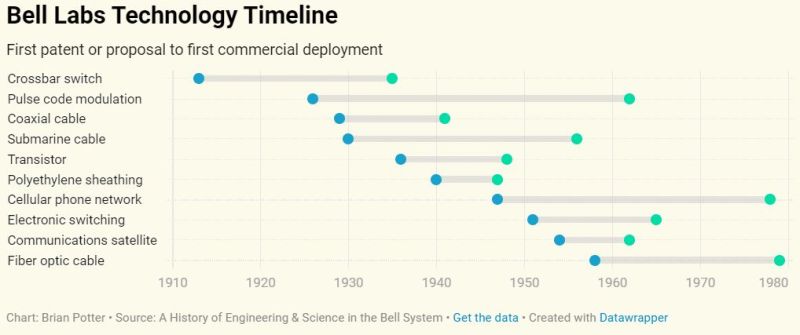

As described in the article by [Brian Potter], one aspect of Bell Labs that made it so successful was that the researchers employed there could easily spend a few years tinkering on something that tickled their fancy, whether in the field of semiconductors, optics, metallurgy or something else entirely. There was some pressure to keep research focused on topics that might benefit the larger company, but that was about it, as the leadership knew that sometimes new technologies can take a few year or decades to come to fruition.

All of this came to an rapid stop following the 1982 court-ordered breakup of AT&T. Despite initial optimism at Bell Labs that things could remain much the same, but over the following years Bell Labs would be split up repeatedly, with the 1996 spinning off of Western Electric into Lucent Technologies that took much of Bell Labs with it being the first of many big splits, ending for now with five pieces, with Nokia Bell Labs (formerly Lucent Bell Labs) and AT&T Labs being the largest two. To nobody’s surprise, among all these changes funding for fundamental and theoretical research effectively vanished.

![A blue LED held up by its inventor, [Shuji Nakamura].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/shuji_nakamura_with_blue_led.jpg?w=400)

Ultimately Bell Labs would seem to have been at least partially a product of unique historical circumstances, especially the highly specialized field of telecommunications before the same transistors and other technologies that Bell Labs invented would make such technological fields something that anyone could get started in. It’s possible that even without court order, AT&T would have found itself facing stiff competition by the 1990s.

The short answer to the original question of whether Bell Labs could be recreated today is thus a likely ‘no’, while the long answer would be ‘No, but we can create a Bell Labs suitable for today’s technology landscape’. Ultimately the idea of giving researchers leeway to tinker is one that is not only likely to get big returns, but passionate researchers will go out of their way to circumvent the system to work on this one thing that they are interested in. We saw this for example with [Shuji Nakamura], who cracked the way to make efficient blue LEDs, despite every effort by his employer to make his research unnecessarily difficult.

If there’s one thing that this world needs more of, it are researchers like Nakamura-san, and the freedom for them to pursue these passions. That, ultimately could be said to be the true recreation of Bell Labs.