Source: Hack a Day

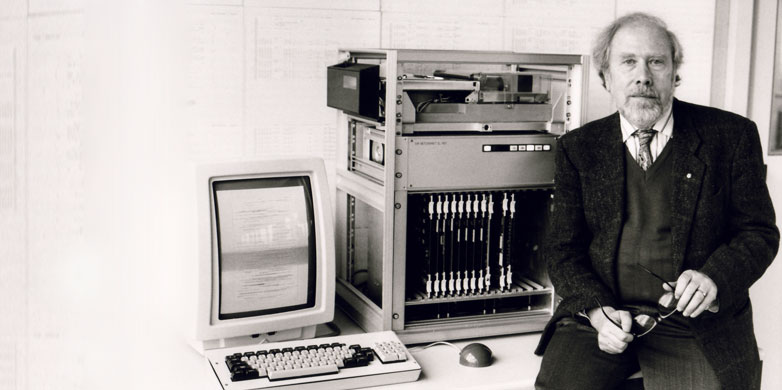

Although perhaps not as much of a household name as other pioneers of last century’s rapid evolution of computer hardware and the software running on them, Niklaus Wirth’s contributions puts him right along with other giants. Being a very familiar familiar face both in his native Switzerland at the ETH Zurich university – as well as at Stanford and other locations around the world where computer history was written – Niklaus not only gave us Pascal and Modula-2, but also inspired countless other languages as well as their developers.

Sadly, Niklaus Wirth passed away on January 1st, 2024, at the age of 89. Until his death, he continued to work on the Oberon programming language, as well as its associated operating system: Oberon System and the multi-process, SMP-capable A2 (Bluebottle) operating system that runs natively on x86, X86_64 and ARM hardware. Leaving behind a legacy that stretches from the 1960s to today, it’s hard to think of any aspect of modern computing that wasn’t in some way influenced or directly improved by Niklaus.

A New ALGOL

Niklaus Wirth was born in 1938, got his Bachelor of Science degrees at the ETH Zurich in 1959, his Master of Science at the Université Laval in Quebec in 1960, followed in 1963 by his PhD in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of California, Berkeley. After this he worked from 1963 to 1967 as assistant professor of computer science at Stanford University.

During this time he would develop the Euler programming language together with Helmut Weber, as a generalization and extension of the then popular ALGOL 60 programming language. He’d also design PL360, a system programming language for the IBM System/360, which was the new computer system for Stanford University. His description of PL360 and the reasoning behind its design were published in volume 15, issue 1 of the Journal of the ACM (Association for Computing Machinery). In it he expresses the hope that PL360 will find use as a tutorial language and to be of interest to the designers of future computers, illustrating how his focus was less on this one IBM platform and more on the development of programming languages in general.

With ALGOL 60 becoming somewhat long in the tooth, there was a call for suggestions for the next ALGOL version, called ‘ALGOL X’ as a placeholder. In 1965 Niklaus submitted a proposal for a set of additions to ALGOL 60, which was rejected due to ‘not being ambitious enough’ for a new ALGOL version. Even so, he was invited to submit his suggestions to the ACM magazine, where it was featured in the June 1966 issue. Niklaus would develop his proposal into an extension to ALGOL 60, called ALGOL W, while his colleague Adriaan van Wijngaarden’s proposal for ALGOL X would go on to become ALGOL 68.

Despite the somewhat competitive nature, there was no bad blood between the parties involved, with the very jovial Niklaus Wirth inspiring for example Van Wijngaarden to quip at the 1965 IFIP Congress that “Whereas Europeans generally pronounce his name the right way (‘Nick-louse Veert’), Americans invariably mangle it into ‘Nickel’s Worth.’ This is to say that Europeans call him by name, but Americans call him by value.”

Pascal And Beyond

Following very much his own course, Niklaus used ALGOL W as the foundation for what ultimately would become Pascal, as named after the famous French mathematician and physicist, Blaise Pascal. First released in 1970, this programming language would go on to fulfill many of Niklaus’ wishes with PL360, in that it became an important teaching tool at schools and universities, as well as being used for programming minicomputers that were making computers ever more accessible outside of big universities and companies.

Pascal saw itself developed by Borland and Apple into Object Pascal, of which the Delphi dialect is probably one of the more well-known. Meanwhile Niklaus had commenced developing a new language called Modula, but after a 1976 sabbatical – during which he spent time at the Xerox PARC labs and got inspired by their Xerox Alto system and accompanying Mesa language – he abandoned Modula and created Modula-2 instead, which saw itself paired with the ETH Zurich-developed Lilith workstation, released in 1980.

This was an AMD 2900-based system, running the, fully written in Modula-2, Medos-2 operating system. From here the 1987 Ceres workstation with its ill-fated NS32000 processor followed, which saw the first use of the Oberon System. Although a Modula-3 was also released, this was not developed by Niklaus Wirth, but rather by Maurice Wilkes who got permission from Niklaus to continue with Modula since Niklaus himself was busy with the Oberon programming language, along with the operating system written in it.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

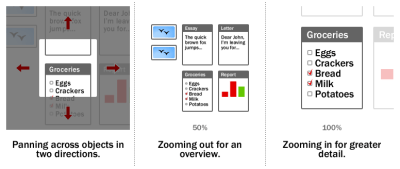

It’s hard to really look at Niklaus Wirth’s career and get anything other than the feeling that he truly enjoyed every aspect of it, whether the challenge of creating a new, better programming language, exchanging ideas with like- and less likeminded colleagues, or increasingly the development of an operating system, experimenting with both Text-Based UIs (TUI) and Zooming UIs (ZUI). Although he noted that software in general by the late 1980s had begun to outstrip the capabilities of the hardware it ran on (referred to as Wirth’s Law), this didn’t deter him from continuing with what he felt was right.

His efforts in progressing the state of computer programming languages had been acknowledged by the ACM in 1984 when he received the Turing Award, along with a range of books such as Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs that were used extensively both in education as well as outside it. Despite languages like Pascal having only a small presence in today’s world of computer science, it’s hard to underestimate the impact that it, as well as Modula-2 and other Niklaus Wirth-designed languages have on the landscape of computer science today.

Much of what we accept as the norm today with imperative and object-oriented programming languages, whether it’s C++, Ada, Java, or any of the hundreds of other large and small languages in existence today, can trace their roots to ALGOL 60. Roots shaped and nourished by Niklaus’ efforts over the decades in making programming languages as simple and effective as they can be. Even today, universities like Oxford continue to use Oberon in their computer science classes, with Oxford even maintaining its own Oberon-2 compiler (OBC).

Where many modern programming languages have a mostly vertical learning curve, Oberon and its predecessors have the property that they are first and foremost simple and elegant, making them excellent teaching tools alongside Niklaus’ books. Although it may seem quaint to teach students to program in a language that they’re unlikely to encounter in a job, Niklaus Wirth has demonstrated throughout the years that it is not the language that matters, but rather the structures and definitions that underlie them.

Rather than developing ALGOL well into the 2000s, he instead chose to design, use and then discard one programming language after the other, dissatisfied with some aspects that he felt certain he could improve upon with the next iteration.

Preserving The Legacy

What is perhaps the biggest risk to Niklaus Wirth’s legacy is digital oblivion, especially considering the fruits of his career. Even while doing literature research on his academic past and the software projects like Oberon (the language and OS) and the A2 (Bluebottle) OS, it’s heartbreaking to see the amount of broken hyperlinks, and the defunct code repository at ETH Zurich for the latter OS. I was able to find an old mirror copy on GitHub by Bernhard Treutwein, in which a number of alternate URL are provided, including an active GitLab instance that appears to be the main repository.

Although much of the information and data does appear to be still out there, there is no good way for newcomers to learn about or get started with these last projects of Niklaus, with generally more information available on Russian-language websites, presumably due to the use of Modula-2 and kin in the Soviet Union and successor states. This fragmented state raises the risk that more and more of this extensive legacy will slowly decay, with few aware of it, and even fewer trying to preserve everything.

Here’s to Niklaus Wirth’s legacy to be preserved forever in its ever-changing, bit-perfect glory, lest it all becomes just a barely remembered Midsummer Night’s Dream.

(Top image: Niklaus Wirth with the Lilith system that he developed in the 1970s. (Photo: ETH Zurich) )